A Certain Slant of Light

Steven Connor

A sound-essay on the idea of twilight, broadcast on BBC Radio 3’s Nightwaves, October 31, 2003.

|

We think of twilight as the mingling of the day and the night, a breathing space, sometimes calm, sometimes menacing, in which neither light nor dark prevails. But the name suggests something odder and more specific than this: not the meeting of light and dark, but rather the copresence of two different lights. As the sun sinks, its light is not steadily withdrawn, but subject to a scattering by the air and dust of the atmosphere. For a short period, this creates a strange, faint flaring of the air, an oblique blaze in things. During the hours of daylight, we have the sun always in mind, even when it is behind a cloud or at our backs. Another word for twilight is ‘gloaming’, which perfectly alloys gloom with glow. The glow of the gloaming, after the sun has gone but something of its light still lingers, seems dispersed or sourceless, as though aching evenly from every surface, as though brightness were falling from the air itself. Evocations of twilight often reach for the ambivalent colours of precious stones, pearl, opal, sapphire, amethyst, which suggest an eerie kind of earthlight, as though objects themselves were giving out their own illumination, stored during the day and given off as day retreats. As the contours of the visible world melt, other, more diffusive senses, start to leak into the eye: touch, hearing, smell. ‘Darkness comes out of the earth’, wrote D.H. Lawrence:

The night-stock oozes scent,

And a moon-blue moth goes flittering by:

All that the worldly day has meant

Wastes like a lie. (‘Twilight’)

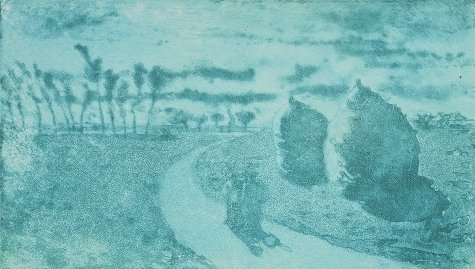

Ted Hughes articulates the sense of panic that can gather through this slow dissolve of substance:

The wind is inside the hill.

The wood is a struggle—like a wood

Struggling through a wood. A panic

Only just holds off—every gust

Breaches the sky-walls and it seems, this time,

The whole sea of air will pour through (‘Feeding Out Wintering Cattle at Twilight’)

At this time, time itself seems to hold back, or be folded over on itself. There are different twilights at different times of the year, with the longest, most luminous diminuendi of light taking place on Northern summer evenings. Yet there is a special, defining kind of strangeness in autumn twilights, where the ‘burnt-out ends of smoky days’ seem to breathe in time with the ebbing year.

Halloween, the earliest of the winter festivals, occurs at a twilight or transition time between autumn, or late summer, and winter. The phrase ‘All-hallown Summer’ refers to the second summer, or the summerly time thought o set in about All-Hallows-tide. The French called this period, which ran from October 9th to November 11th, L’été de St. Martin, or St Luke’s Summer. Shakespeare’s Prince Hal bids farewell to it as a ‘latter spring’ (1 Henry IV, I.ii)).

Halloween is a disguised survival of the Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the end of summer, the gathering of its fruits, and the approach of winter. It was a time when the veil separating this world and the supernatural otherworld was at its thinnest, as demons and spirits sensed the waning of the powers of summer light and celebrated the coming dominion of the dark. Bonfires were burnt and walls daubed to keep spirits at bay. Strangely, at such times, the usual horror at the dead’s approach would give way to hospitality; doors would be left open, and tables spread for ghostly revenants. In some places in Scotland, Halloween was known as ‘gate-night’, after the practice among the young of removing gates from fences, as though to signify the opening of passage between worlds. The twilight time of Halloween is therefore not just the breaching of the dam between this world and the next, but a kind of semipermeable membrane between them. And yet, perhaps the garishness of modern Halloween is intended to substitute light flaring against the dark, and the definiteness of the witching hour, for the dimmer, more tangent time of twilight.

The meeting of worlds of belief is a feature of the festival of Halloween itself, which is the result of the overlayering of pagan celebrations with the feast of All Hallows or All Saints, which the Christian church decreed would take place on November 1st, no doubt to signify a new Christian morning after the pagan night before.

Anthropologists have made us familiar with the idea of the rite of passage between different states or conditions, and the special meaning attaching to liminal or threshold experiences in traditional cultures. But it is the modern world which seems to have a special fondness and feeling for the threshold, for intervals of recoil, or times at which time holds back. When in 1874 Wagner completed his reworking of the Norse epic of the end of the world, he translated the word Ragnarok, the doom of the gods, as Götterdämmerung, the turbulent twilight of the gods. From Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols, and the Celtic Twilight of the 1890s, through to our contemporary fascination with the condition of being ‘post’ – postmodern, postindustrial, even, intriguingly, ‘post-contemporary’ – we seem to have developed a special affinity with the conditions of interlude and aftermath, for what Matthew Arnold called ‘wandering between two worlds, one dead/One powerless to be born’. When T.S. Eliot, the opening lines of whose ‘Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ link twilight and ether, referred to life as ‘this brief transit where the dreams cross/The dreamcrossed twilight between birth and dying’ (‘Ash Wednesday’), he might almost have had in mind to the anaesthetic condition known as ‘twilight sleep’, brought about by a mixture of morphine and scopolamine, in which many mothers, including, it is said, Queen Victoria, gave birth up until about the 1920s.

Perhaps the particular resonance of the twilight state, of that which simultaneously wanes and remains, has also to do with our habituation to the technologies that increasingly allow us to hold time in suspension. From its beginning, the art of photography has been a kind of twilight art. Far from being impoverished by its lack of colour, photographs opened up a spectral new world of grey tones, a kind of parallel world to our own. The particular affinity of ghosts and the new art of photography seemed to suggest a lingering of the belief that to die must be, as the classical world thought, to become ‘a shade’, and thus to be made over to grisaille. Moving pictures, when they came, did not dispel, but rather multiplied and prolonged the ghost-effect of photography. For our moving pictures all depend upon the principle of retinal persistence, the lingering of images on the eye after their source has vanished, which is itself a kind of twilight state repeated at 24 frames a second. In music and film, we have discovered a new relish for the effect known as the fade-out.

There are many modern painters and writers who have made the twilight their home: from Chopin’s nocturnes, Whistler’s paintings, and the extraordinary enlargement of the repertoire of dimness in the late works of Beckett, especially his elaborations of the ‘leastmost’ in his Worstward Ho. It is as though the fading of power were itself a source of its replenishment. James Joyce ended his two greatest books with long fade-outs into nothingness, leaving the reader suspended in his cunningly wrought ‘twosome twiminds’.

The slight tipsiness of the earth’s solar orbit makes twilight a Northerly phenomenon. Twilight is not the time of inversion, the world turned upside down; it is time on a tilt. Perhaps it produces sensibilities that weary soon of straight-up-and-down things, of once-and-for-all, four-square perpendicularities, are inclined to see things anamorphically aslant, and have a taste for the late, the not-quite, the trick of the light, the all-but, the betwixt and between. This refractory wryness, or angled Saxon attitude, prizes what pales yet persists, what lingers and lasts out, over the blaring conflagrations of noon. Emily Dickinson, who was one such ember spirit, wrote of

a certain slant of light,

On winter afternoons,

That oppresses, like the weight

Of cathedral tunes.Heavenly hurt it gives us;

We can find no scar,

But internal difference

Where the meanings are.

There is a shiftiness in this time or trick or treat. Samuel Beckett, that most unlikely literary athlete (leg glance specialist, slow left arm spin), used to compile imaginary rugby teams made up of writers and artists living and dead. When a friend raised an eyebrow at the selection of the almost blind James Joyce in the crucial, hinge position of fly half, Beckett replied glintingly; ‘when it’s the end of the game, in the fading November light, you need someone tricky to make the play’.